What Is a Codependency Triangle, and How Do You Break Out?

What is a codependency triangle?

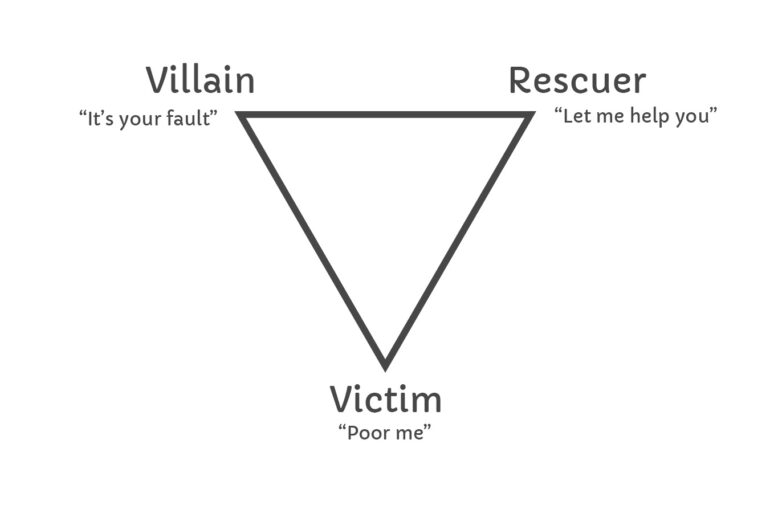

A codependency triangle is also known as a drama triangle. It’s a model developed by Dr. Stephen Karpman in the 1960s to describe a pattern of roles that he saw people playing in dysfunctional relationships.

The triangle itself is made up of three different roles: the rescuer, the victim, and the villain (sometimes also referred to as the persecutor). It can involve two or more people, with each person playing different roles and shifting between them in response to each others’ behaviour. Being locked in a drama triangle is a form of codependency, because whichever role you’re playing, you need the other to stay in their role in order to unconsciously get your psychological needs met. I’ll talk more about those needs below.

Playing out a drama triangle can feel really tough to break out of – many of us are unaware we’re even in one for a long time – because to do so means letting go of some of our oldest, unconscious coping strategies. Often, the roles we play in our adult relationships reflect the roles we learned to play as children in our family system (or saw those around us playing), and changing the way we relate to others can take some time and patience.

Let’s explore each role in the drama triangle, and then I’ll give some ideas for breaking out of it.

Codependency is a symptom of disconnection. Learning to reconnect with yourself and the other person, in an embodied way, is a really important skill to learn.

Grab my top ten simple tools you can use to do just that, transforming vulnerable moments into deeper presence and connection:

The Rescuer

Being in your inner rescuer can look like always being the helpful one. You might often feel certain that you’re the person who can fix things for others, even when nothing you do seems to help in the long term. Perhaps you’re the person everyone comes to for help – but it’s never reciprocated, and instead you often feel drained and exhausted, as though no-one is taking care of your needs.

If you identify with your inner rescuer, you’re likely to attract people who will drain your energy. These are the kind of people who will always be complaining and needing something, while never taking any steps to help themselves. They’re not actually invested in improving their situation, and so nothing you can do will ever be enough.

But that doesn’t stop you from wanting to help, because you still care about them, and you really do want their situation to improve. And maybe this time things will be different? Maybe this time they’ll really listen to your advice? You might find yourself telling yourself that your care and love might be the thing they most need.

While taking care of people who need help is generous and kind, rescuing is different: there’s an unconscious need to be the person who can make everything better, and your self-worth is really invested in being the one to help. One of the pay-offs of rescuing is that it means you’re taking the focus away from yourself and placing it on the other person’s problems, which can be a really smart way of distracting yourself from things in your own life which may feel challenging.

And here we can begin to see the vulnerability that rescuing protects you from: feeling needed and wanted feels safe. Often, self-worth becomes so entangled with feeling needed that it can feel impossible to let go of wanting to help, even when it’s at the expense of your own wellbeing. For those who struggle with their own self-worth, feeling needed by another can be a huge boost.

The problem comes when the pent-up resentment and frustration from abandoning one’s own needs begins to take its toll. When this happens, someone in the rescuer role may switch to become either a victim or a persecutor, and enlist someone else to rescue them.

The Victim

Stepping into the victim role can feel like the world is against you and nothing will ever change. The victim is a place of, “poor me!”

You might find yourself blaming your life circumstances or other people when things don’t go your way. You might often feel like you don’t really have any choice in things – that life is just happening and you are powerless to really make changes, like this is just “the way things are.” You might find that people offer you help or advice, but none of it seems to be relevant or useful to you, or even if you try to take it, nothing changes.

It’s true that there are always things we are powerless over. But if you’re occupying the victim position, it becomes a very all-or-nothing mindset, and one which isn’t willing to act on advice or try different alternatives.

You might even find yourself feeling resentful of the people who care the most, or deeply mistrustful that they really want to help. Perhaps you push them away without even realising why.

It can feel super vulnerable to really accept help if you’re caught in the victim role, because that means taking responsibility for where you’re at, and committing to making a change. That’s a big step, which can require confronting some deep fears: that you might fail if you try, that you might be abandoned if you ask for help, or even that you might succeed, but lose your identity in the process.

And so staying in the victim role keeps you safe from these fears. It also allows you to cleverly shift the responsibility for your own circumstances on to someone in one of the other two roles: a rescuer who can keep trying to fix everything, or a villain who can take the blame for everything. This explains why the rescuer can never succeed – because someone in the victim role needs to stay in the role in order to avoid their fears, and avoid the vulnerability of making a real change.

The Villain

The final role in the drama triangle is the villain. This is the position where we blame, judge, and criticise others. It can look bullying, threatening, or ordering, without offering any real guidance or assistance.

Playing the villain is a bid to feel powerful, by blaming and shaming others. In this way, it reveals similar challenges with self-worth that we see in the other two roles – in fact, in one sense, all of these roles are ways of coping with and mitigating against low self-esteem.

In a conflict between two people, the villain is often the role that either the victim or the rescuer will end up in when the original roles inevitably fail to resolve the situation.

A common way that this can go is for someone in the victim role to enlist a rescuer. The rescuer starts to give their time and energy to fixing the victim’s problem, trying everything they can to help. When the rescuer realises that they are giving more than they have the capacity for, they begin to feel resentful and withdraw from the situation – or they might simply put a boundary in place and tell the victim that they don’t want to discuss the problem any further. When the victim notices this, they may start to blame the rescuer instead. They may become judgemental or angry, taking out their frustrations on the rescuer. In this way, the victim steps into the role of the villain.

From here, the rescuer may themselves switch to the victim role (because they now feel hurt by the victim-turned-villain) and seek out a new rescuer. And the dance continues!

How do you know if you’re stuck in a codependency triangle?

You might recognise yourself in any of the roles above – or all of them! If you’ve played one (and most of us have at some time or other), chances are you’ve played all of them to some extent.

Here’s some signs that may indicate that you’re in a drama triangle:

- It feels as though there’s often a lot of drama in your relationships, with big ups and downs

- You find yourself often the one helping others, without receiving the same support in return

- You often feel helpless about your situation and as though there’s nothing you could do to change it

- You find it very difficult (or impossible) to feel and express anger in healthy or productive ways

How to break out of a codependency triangle

So what can you do if you notice that you’re stuck in this cycle?

If you recognise that you’ve been playing these roles in your relationships, or you’ve been dragged into others’ drama triangles, the first thing to do is to notice it with compassion.

All of the roles in the triangle appear because there is a deeper need that we’re not having met: for validation, for affection, for safety, for peace. We unconsciously try to get these needs met by acting out drama or seeking codependent dynamics, which may work in the short-term, but over time feel draining and inauthentic.

Bringing awareness to this pattern, and noticing what roles you – and others – are playing is the most important first step.

The the most important thing to realise is that it’s the rescuer who keeps the whole cycle turning: the rescuer enables the victim’s powerlessness by trying to solve and fix their ‘problem,’ and in this way the victim passes on all responsibility to the rescuer. This allows the victim to keep on blaming, rather than acknowledging their own power and responsibility and making a change. This becomes clear when nothing the rescuer says or does really seems to make a difference, and yet they are unconsciously encouraging the victim to stay in their role by offering sympathy to the victim’s complaints.

How to stop rescuing

While it’s important to be aware of stepping into a rescuing role, wanting to solve and fix another person’s problems to bolster your own self-worth, that’s not to say that there isn’t a place for genuinely helping those who genuinely want your help. One way to think about this is to become a supporter rather than a rescuer. You can support those in your life to make the changes they want to make, when they are clear that they want your support, without stepping into rescuing.

One simple way to do this is to start asking more questions the next time someone talks to you about a problem they have – questions such as, “How would you most like to be supported right now?” or even, “Do you want my support in this?” This can encourage the other person to think about what it is they really want from you, and then you can decide whether you are willing to offer that to them.

How to stop playing the victim

If you’re more familiar with the victim role, then your task is to recognise the power and agency you do have in your life, even if it only seems small at first, and determine the steps you can take in your life to change your circumstances in ways that would feel better for you. This will likely mean facing some fears, and it might mean having some difficult conversations and reassessing what’s important to you. It may well also mean asking for genuine support from people around you to make specific changes in your life.

How to stop persecuting

One way to work with the villain role is to reframe it as being a challenger. Instead of blaming, shaming, and criticising, how could you offer supportive challenge to those around you instead? Giving constructive criticism and feedback can be incredibly valuable when it’s done with the other person’s consent and genuine best interest at heart, and in this way the aggressive and threatening energy of the villain can become transformed into something that is of service.

Learning to do this means recognising the difference between power over and power with – while the persecutor operates by finding power over others, here the shift is towards cooperation and finding a sense of power by working relationally with the other person.

Something I’ve learned on my own journey, and in my counselling work, is that accessing the deeper needs and fears that motivate each role in the triangle is the most powerful way to really make changes.

This can be done in a really gentle and safe way, opening a dialogue with the parts of yourself that really need some attention and care, and starting to meet those needs in a healthier way.

If this is something you’re curious to know more about, click here and let’s see if I could be the right person to support you.

I’d like to work on breaking the drama cycle! Do you have any courses on this specifically?

Hey Sjanie! I don’t have any specific courses on this, but maybe that’s something I could create in the future. Which positions on the triangle feel most familiar to you?

Mostly rescuer, sometimes victim, occasionally persecutor!